Voxelgram 2 - Interview with Developer Łukasz Krasniewski of Procedural Level

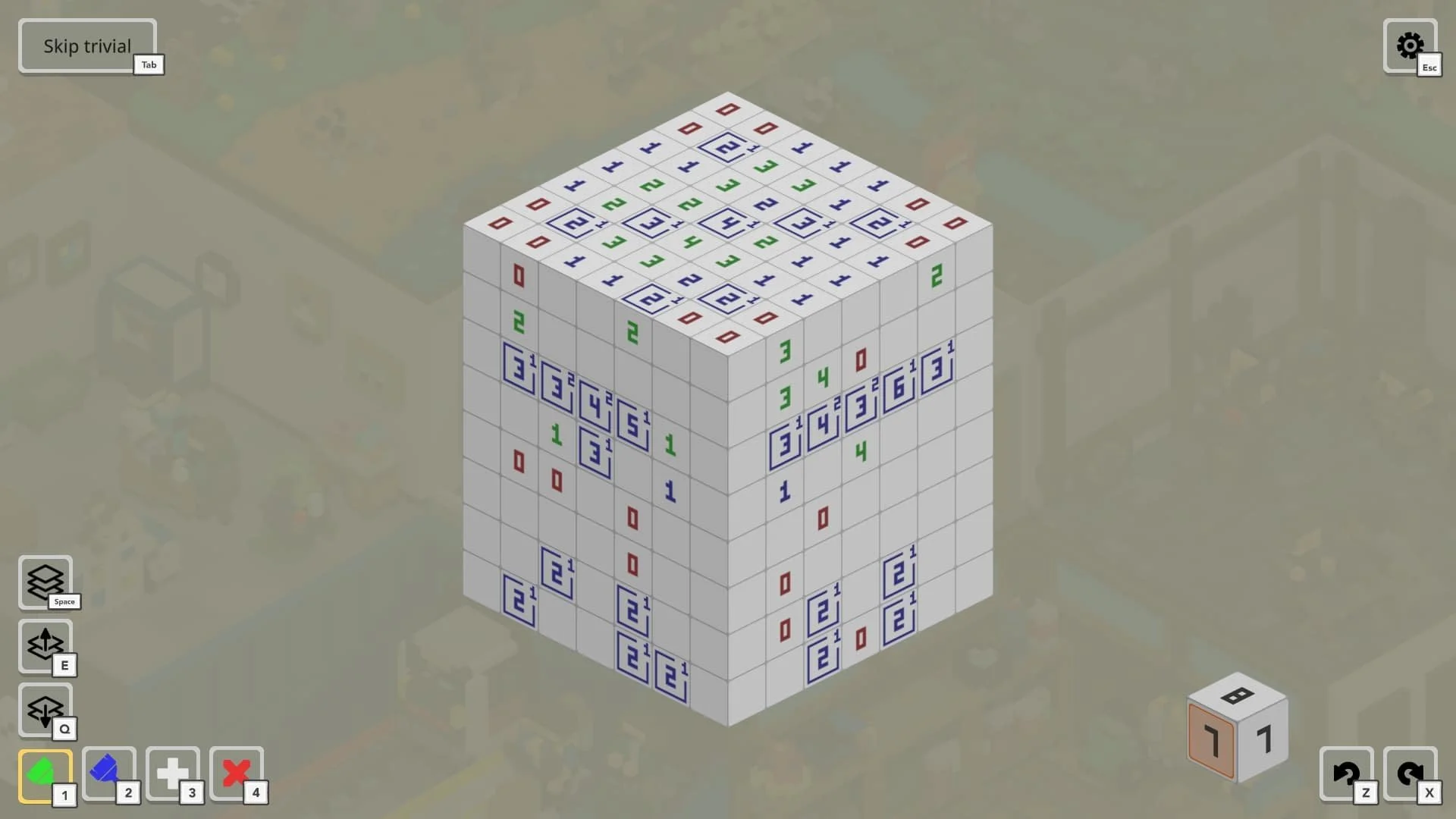

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

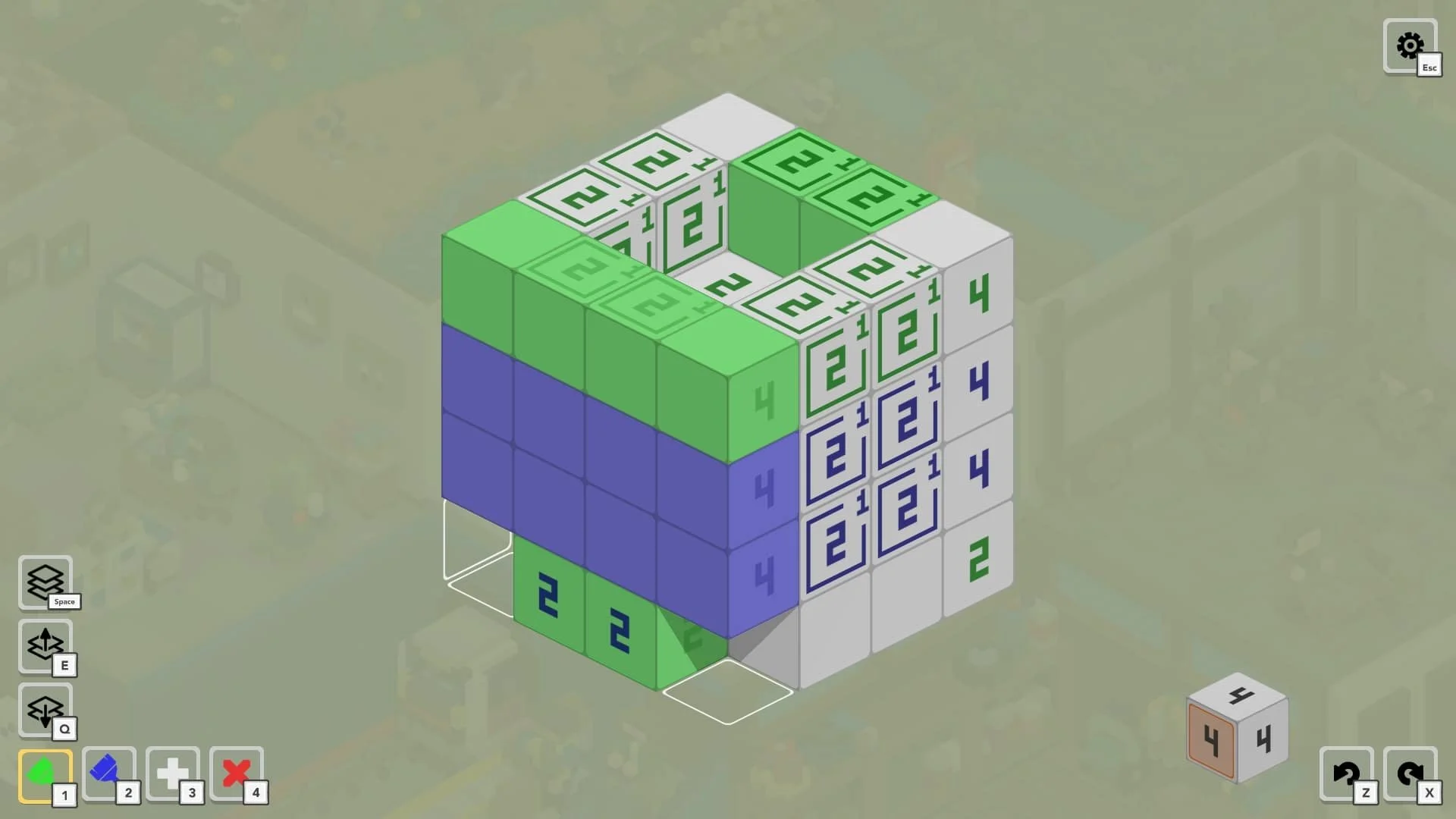

Procedural Level released the 3D nonogram game Voxelgram 2 on December 14. This sequel iterates on the original with a new dual color mechanic, where puzzles aren’t solved by just chiseling away cubes—the player now has to determine what color remaining cubes are as well. I was very excited for this release as soon as I heard about it, as a big fan of the first game.

Other 3D Picross games that feature two colors, including HAL Laboratory’s Picross 3D: Round 2, give players clues for both colors on any given cube face. Voxelgram 2 puts its own twist on the rules: it only offers clues for a single color on any face. This makes for an interesting wrinkle on the already familiar format as the puzzles require an extra layer of consideration to solve.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

Like the first game, the puzzles are organized into dioramas with varying themes that get filled out as each solution reveals a new object in the scene. There are 250 puzzles, and as a bonus, owners of the first game also get access to two-color variants of all of the first game’s puzzles. Procedurally generated puzzles and Steam Workshop support round out the package, offering endless replayability.

I love Picross, its 3D variant, and Procedural Level’s original Voxelgram. This new one is even better, a solid 9/10 for me.

Łukasz Krasniewski, the solo dev who drives Procedural Level and created both Voxelgram games, was kind enough to participate in an interview. He gave me a lot of insight into his process and the design of Voxelgram 2. I’ve made small edits for clarity in the answers below.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

Sam Kahn, for The Geekly Grind (GG): Could you please tell me about yourself? How did you get into game development? Were you a software developer before working on the first Voxelgram? What led you to found your studio?

Łukasz Krasniewski (ŁK): Hello, I'm Łukasz from Poland. I never worked as a regular software developer, doing websites or other business-focused software, but I've been working as a programmer making games for about 9-10 years now. I was lucky enough to get an internship at CD Projekt Red, right after University, where I spent 4 years on Gwent. I left when I realized that I would like to try and create my own game, and I was playing Depixtion and Pictopix at the time, so I came up with the idea of 3D Nonograms that I thought was doable. After Voxelgram, I went back to work for large and small game dev companies. That changed in December last year, when I finally decided it was time to try and go full-time indie again. I like to have an impact on the design of a game, and I like game genres that are a bit less popular, so going indie seemed like the best way to have a chance of working on them.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: Do you work on your games full-time? What are the challenges for you as a solo developer?

ŁK: Design/prototypes happened while I was still working full-time, but actual development for both games was full-time. Depending on how the release of Voxelgram 2 goes, I hope I will be able to stay full-time indie for the duration of the next project. Working solo means that I have to do everything that would usually be done by someone else in a team. Marketing, contact with stores, social presence, patch submissions, and creating assets. I'm a programmer, so everything outside of code is a challenge to me. But it is also the only viable way, I think, to create niche games like Voxelgram. And I really enjoy it this way.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: Tell me about the development of Voxelgram 2. Did you take a break after the first game? Did you start from scratch or build upon the first game’s code base?

ŁK: Voxelgram 2 development started soon after releasing the first Voxelgram. At least conceptually. I wanted to make a sequel, but I didn't know how to make it unique yet. So I would come back to it every few months, prototype some features, realize that I still don't have a clear idea what I want to do, and scrap it. Although each time this happened, I would try to integrate whatever came out of those prototypes into the first game. For example, DLC puzzles are actually puzzles I was preparing for the sequel. I thought that maybe going for larger dioramas and larger puzzles would be enough to make the sequel distinct, but it wasn't. So the development of Voxelgram never really stopped, but it was very slow at times. And I've worked full-time for most of that period, so I didn't have that much time to work on it.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: What lessons did you learn during the first game’s development, and how did you apply them to the new game? What feedback was most meaningful for you from the players of the first game as you developed this sequel?

ŁK: I've got lots of great feedback from players. Multiple quality of life features were added because someone suggested it, or just mentioned that something is frustrating or annoying. Like hints are rotating towards the camera because they have frames, because people would mention that it's easy to miss/hard to read them sometimes. There is the "load last valid state" option, as some puzzles would take a long time to finish, and making a mistake often would require a full restart or long investigation on where the mistake happened. I've kept that all in mind while developing the sequel, paying attention to have all the features in on release day and some more.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: Seeing a completed diorama is a great reward for finishing a set of puzzles. What led you to design the puzzle groups as dioramas? How do you choose the themes for each diorama, and then determine what objects you want to represent?

ŁK: I think I got the idea from the Pictopix game, which has Mosaics. Larger images, created out of smaller puzzles. I really like that idea, it makes level selection more interesting. But it created a challenge, as now I had to come up with thematically connected sets of puzzles. They had to be similar in size and shape complexity to avoid massive difficulty spikes. And they needed background scenery. In the first game, I also set a constraint of 10 puzzles per diorama, which meant that I had to drop a few ideas as I couldn't come up with enough objects. I've moved away from that limitation after adding Workshop support.

New themes, I pretty much pick at random. Whatever comes to my mind, I try to create 2-3 models to see if it can be done, and then try to expand on it. I would often browse forums dedicated to miniature painting, diorama creation, or even LEGO sets for some theme inspirations. Sometimes it would be based on a place I've visited, a story I've read or watched. And lots of Wikipedia/Google image searches, to find objects that would fit the theme that I worked on.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: How did you arrive at the final visual style of the individual models?

ŁK: My first idea was to use regular 3D models that were covered by voxels. But that didn't feel right. Also, early in the prototyping phase, I was experimenting with how to transition between dioramas in the main menu, and I came up with the current fade-out/fade-in transition, which locked me into voxel models. And that allowed me to show puzzle progress on dioramas.

GG: What is your approach to designing the puzzles into the voxel models? How do you decide where to place hints, and what rules do you follow to scale difficulty? Do you do this manually, or have you written algorithms to help craft the clue placement?

ŁK: Hints generation is fully automatic, it allows me to ensure that each puzzle can be solved without guessing. It also takes seconds to generate all the hints, instead of hours, if I were to do it manually. Doing it with an algorithm also allowed me to have a relatively consistent feel and difficulty between them. The way it works is that the algorithm starts with all the hints, tries to solve it. If it's solvable, it removes some hints and repeats it until it hits a minimal viable set. Removal of hints follows some rules, like removing low values first, trying to keep hints more common on specific axes, so that you don't have to rotate the puzzle that much, etc. And it also enables player-generated content.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: What advice do you have for players designing their own puzzles for Steam Workshop?

ŁK: Symmetry leads to boring puzzles, but it can be avoided by placing "random" blocks here and there, or, in the case of Voxelgram 2, adding different shades of colors. Long flat surfaces in single colors are also not great. It's a good idea to avoid empty lines when possible. But in general, focus on creating a model that looks interesting, and it will usually lead to a fun puzzle.

GG: I found the design of Voxelgram 2 interesting in how clues can be partial. In games such as Picross 3D, when two colors are present on a row or column, a clue will always give you a number for both colors. In Voxelgram 2, players have to cross-reference clues from a row and column to determine logically if there will be a gap or a different color on intersecting blocks, as the clues consider a color change and a gap to be the same. What led you to create that differentiator in your design? How did you iterate to reach the final mechanics, and how long did it take for it to “click”? What other kinds of interesting ideas did you discard and why?

ŁK: Fun fact is that I wasn't even aware of Picross 3D when I started working on Voxelgram initially. Which is why rules are slightly different, with numbers instead of shapes, to indicate gaps. So when I started working on the sequel, I wanted to evolve Voxelgram instead of cloning the Picross system. But I did consider placing hints of both colors on the same row. I quickly found out that it was creating too much visual noise, and it was much harder to read on smaller screens. Voxelgram max puzzle size is 15x15x15, which means that hints like 12^3 are possible, so if there were 2 hints on 15 a 15-block-long line, it would be tiny even on 24'' screens. And I felt that this way it played too much like the original Voxelgram.

I was thinking about how multiple colors work in 2D, and how it leads to some line interactions. That interaction part is what I wanted to have in Voxelgram 2 as a main differentiator. And with the visual limitations, the only path forward was to have the current hints system. It took me a few weeks to figure out how to write an algorithm that will generate hints for this system and to ensure that it actually generates enough interactions to keep it interesting. And it also took me a few weeks of playtesting to convince myself that this is a good and fun idea. But I wasn't 100% sure until I invited a few people for playtesting. I was lucky to land on the idea that worked pretty much instantly; I didn't have to iterate on the design of it that much.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: With the availability of the first game’s puzzles with the two-color system in the new game, how did you go about refactoring the old puzzles?

ŁK: I had to change a few of the model shapes and add some colors to make them solvable with new rules and to make sure that colors are balanced. Some of the puzzles in the original form could be solved; the algorithm would make them all blue, for example.

GG: What was behind the decision to exclude any marking tools in Voxelgram 2?

ŁK: I don't think that it's needed. Lines are relatively short, and there aren't deep recursive tactics like in 2D nonograms, where you have to mark a few lines before you find that one cell that you can paint. And it also simplifies the control scheme.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: You did this for the first game, so this is a broader question. What were the challenges in adapting the games for controllers? I assume mouse controls came first. Is this correct?

ŁK: I had some experience with a previous game I've worked on, where we had some issues integrating the controller at a later stage of development. So to avoid this with Voxelgram, I've actually had support for controller from the beginning. Supporting multiple input devices forces a slightly different architecture of code. The main challenge with the controller was how to control the camera and the cursor in 3D space at the same time and have the slicer supported. I also wanted to avoid input that would require holding multiple buttons at once. I actually prefer playing it on a gamepad these days; most of my playtesting is done on a Steam Deck.

GG: Being noticed through the noise in online game marketplaces is tough. Did you aim to self-publish from the beginning, or is that a decision you made further into the original game’s development? How have you evolved as a publisher between both games to improve your visibility? What advice would you give other developers who decide to self-publish?

ŁK: I wanted to self-publish from the beginning. I wanted to experience the whole process, but I also thought that with puzzle games, there isn't really a space left for publishers. This isn't the best-selling genre, and I think it's hard to market it, which led me to the conclusion that going with a publisher wouldn't work for me, if I were even able to find one. I was considering going with a porting company for the Switch release, but I ended up doing it myself. I was almost sure that I would want to push updates a few years into the future, and I wasn't sure if I would be able to do that if someone else took care of the porting. And doing it with Unity turned out to be quite trivial. And I think that is also my advice for others, if your game is in a small niche without much competition, or just with a small audience, it might not be worth going with a publisher. If you make a good game, people will stumble upon it sooner or later, I think. Voxelgram had its best months about 5 years after the initial release.

Voxelgram 2. Credit: Procedural Level

GG: What other games do you like to play, aside from the Picross/Nonogram games that inspired you? Do you have other favorite puzzle types? Do you see yourself making another kind of puzzle game—or something in an entirely different genre—sometime in the future?

ŁK: Other than Nonograms, I really like puzzles with open-ended solutions. Zachtronics games are ideal examples of that. I also enjoy puzzles that require some tinkering, but provide you with enough hints that it doesn't feel like you are walking blindly, like Tametsi. Outside of the puzzle genre, I like automation games and grand strategy from Paradox. If I were to make a game outside of the puzzle genre, it would probably be some kind of strategy or automation game, that is, if I were able to come up with an interesting idea that can be done solo or with a tiny team. Or maybe something like one of the Zachtronics games.

I want to thank Łukasz for taking the time for this interview and providing such thoughtful answers. Be sure to buy Voxelgram 2 on Steam! It’s a must-play for nonogram fans.